Thunder Bay

Lakehead

In 1671, the French map Carte des Jésuites had an unnamed river on the western shores of Lake Superior in New France that was referred to as "R. [La rivière] par où l'on va aux Assinipoualacs à 120 lieues vers le Nord-Ouest", The river by which one travels to the Assinipoualacs 120 leagues to the north-west. A league is 3 miles, and the Assinipoualacs were likely the Assiniboine Nation, migrating slowly westwards to become a plains people but at the time probably somewhere between present-day Winnepeg and Brandon, Manitoba, about 360 miles to the north-west of the mouth of the river that had no name.

Within ten years the river had acquired the name Kaministiquia, a corruption of Gaa-ministigweyaa(-ziibi), (a river) with islands, and the land around it was referred to as Kamanistigouian. On August 23rd, 1681, a decree was issued from the Souverain de la Nouvelle-France in Québec which is the first document to mention either Kaministiquia or Kaministigouian. It was an order to spread the word amongst those living in the bush that King Louis XIV was granting amnesty to the coureurs de bois.

The runners of the wood, les coureurs de bois, had their start in 1608 when Samuel de Champlain founded his permanent Habitation on the ruins of Stadacona at present day Québec City. In order to ingratiate himself, and therefore the French, with the locals, he would send young French men, boys really, to live amongst the first nations folk and learn their languages and culture. One such boy was eighteen-year-old Étienne Brûlé who had been living in New France since he was sixteen and was anxious to volunteer to live with the Algonquins. So Champlain brokered a deal with Iroquet, a chief of the Petite nation, to exchange Brûlé for a young indigenous man named Savignon. As it happened, the Petite people wintered at Huronia, but that story has already been told. In any event, with an increasing number of Frenchmen totally at home in the bush and amongst the people who owned it and the furs therein, it was only natural that they would be sent deeper and deeper into the woods to explore and exploit existing trade routes. This had the intended effect of cementing New France' claim on the new world to a surprising distance inland, to the detriment of the Dutch who were really only a player on the Atlantic seaboard. But it was also the first determined and detailed exploration of the land that would become Canada, eventually pushing as far west as the Pacific Ocean and as far north as the Arctic Ocean, but bypassing the Hudson's Bay watershed, which we'll get to in a bit.

But the coureurs were mostly operating without official licenses. La Compagnie des Cent-Associés, The Company of One Hundred Associates, had had a monopoly over all of the fur trade out of New France ever since 1627. They, in theory, ceded their monopoly to all habitants (colonists) living in New France, but in reality, only the wealthiest habitants, la Communauté des habitants, received any licenses which they then doled out as they saw fit, and under terms which they found favourable and could change retroactively. The intention was to control the numbers of colonists out in the field at any one time to ensure that a sufficient number were keeping the colony running. Operating outside of this monopoly, granted by the King, meant that you were technically a smuggler. Penalties for smuggling furs ranged from simply being granted a congé (license) with its associated taxes, to having your goods confiscated, to being subjected to la fletrissure (branded with a red-hot Fleur-de-lys iron) or you could get much of the above and hanged into the bargain. Even if a runner got a congé he was still not working directly for the associates but rather for an aristocrat of some sort and was likely to face some kind of arbitrary treatment. But the potential payback was great, and many people were lured into the life of the coureur.

Two of the more notable runners were Pierre-Esprit Sieur de Radisson (Sir Radish) and Médard Chouart Sieur des Groseilliers (Sir Gooseberries). Radisson arrived in New France in 1651 at the tender age of 11 (although the records are a little sketchy) and almost right away, while hunting water birds near his home in Trois-Rivières, was kidnapped and adopted by a Mohawk party which was raiding north from their home far to the south on the Mohawk River. The taking of wards from other groups was common practice at the time, to replace people lost to disease and war. So the young Radisson was not so much a prisoner as simply an honourary Mohawk, complete with a brand new mother, father and family who loved him like a son and brother.

But his heart wasn't in it. While out hunting with his new Mohawk friends he was intercepted by a party of Algonquins, themselves raiding far to the south of their home. They killed the Mohawks immediately, but Radisson, who quickly changed shirts, was escorted back towards Trois-Rivières. The problem, of course, was that they were still deep in Mohawk territory. Radisson's new party was captured, and the Algonquins were killed out of hand. As a former Mohawk, Radisson was taken home and subjected to ritual torture, to see what he was made of. His Mohawk family were advocating mercy for him, going so far as to offer compensation to the families bereaved by Radisson's defection to the Algonquin. They advised Radisson to be brave, as cowardice meant death, but not too brave, as that also meant death - an exceptionally brave enemy would be honoured by having his heart eaten. So Radisson was just the right amount of brave, singing loudly while his fingernails were pulled out one by one, taking it in stride as he was burned while tied up to a scaffold, having red-hot daggers thrust through his foot, and, of course, witnessing large numbers of other prisoners going through much the same process only they weren't former Mohawks so their treatment was not so gentle.

Radisson survived, his torture being really more of a punishment, and he was taken back into Mohawk society, although he was no longer totally free. When he accompanied a group of warriors to trade with the Dutch at Fort Orange, the governor offered to buy him and give him his freedom, but Radisson declined, preferring to return to his (Mohawk) family. And then he changed his mind, escaped, and returned to Fort Orange where he met a Jesuit by the name of Antoine Poncet who packed him off to Holland to learn how to be a missionary. Holland at the time was Protestant (Calvinist) to the north and west, Catholic to the south and east, with a smattering of Judaism, Islam and miscellaneous throughout. But the country's unifying theology was capitalism. So it was really no surprise when, after a three year stint as a Jesuit missionary in New France, Radisson decided to hang up the black robe and hook up with his brother-in-law Groseilliers for a trading trip around Lake Superior.

The partners had a one year license from the Governor of Québec, Pierre de Voyer d'Argenson. There was no chance of taking sufficient provisions for a year in the bush; in fact, the coureurs de bois would pack somewhat light on the provisions, preferring instead to double down on the trade goods, which were worth their weight many times over in food, presuming, of course, the goodwill of the Ojibwe villages they would encounter. Luckily, the Ojibwe were overflowing with goodwill towards French traders. Especially the women.

In the 17th century being an Ojibwe male was a very dangerous occupation. There were wars, animals, and various other forms of misadventure that resulted in quite the surplus of Ojibwe females. And being a surplus female was not a good life. Polygamy was a common way for the remaining men to try to help out, but there is a limit to how many mouths a hunter can feed and defend. So whenever some French coureurs happened along, it became de rigeur for them to be offered and to accept first nations wives, who were very welcome as a sort of all-access pass to the interior, in addition to their other charms. Over time, populations of children born to these unions became known as the Métis (a word having various connotations referring to those of mixed parentage) whom we'll revisit another day. In the meantime, it suffices to say that Radisson had missed this particular lecture in seminary.

When they happened upon an Ojibwe village in the spring of 1660, Radisson and Groseilliers gave the men kettles, hatchets and knives. The women received awls, needles, combs and paint. The children received brass rings, bells and beads. And for the Frenchmen... the ladies were literally bending over backwards to show the newcomers their gifts. When Radisson, who was arguably a Jesuit priest, failed to comprehend what was on offer, the village elders told him bluntly that as long as he and his partner did not trade with the enemy Dakota then they were free to enjoy the company of any and all unmarried women that they fancied. Radisson's memoirs remain vague on what happened next, except that when he and his partner returned to Québec with a bounty of furs they were a few days over their one year license and suffered draconian taxes as a result. So off they went to the Thirteen Colonies to see if the British would underwrite their next adventure.

In their travels amongst the Ojibwe, the pair had heard repeatedly about the salt sea to the north, and all of the furs to be had in Cree territory. This could only be Hudson's Bay, and probably James Bay in particular. So they mounted two unsuccessful attempts to sail into James Bay with aid from their new Bostonian friends. Boston at the time did not have the resources to launch a successful voyage of this type; kind of the moon shot of its day. So the runners went to England for a year (1665-66) to petition King Charles II for help. That was granted, and three years later the team returned to England, minus one ship but loaded down with furs. Now they were looking for a more permanent charter.

But British politics at the time was a tricky thing. Radisson and Groseilliers wanted very much to form a company to directly compete with the Cent Associés. But they needed money and a royal patron. Money was surprisingly easy: they had returned with proof that they could pull it off, and so the City of London would underwrite their next project. As for a royal patron - King Charles had just signed the secret Treaty of Dover with France against their common commercial enemy, the Dutch. It would be awkward for him to play Perfidious Albion (foul) with the French at that exact moment. And that brings us to Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland.

Prince Rupert was the King's first cousin and a war hero to boot. But he was also a dick and no one liked him, especially the King. Nonetheless he had three things that were strongly in his favour for becoming a royal patron of the new fur company: he lived very far from Britain in Bohemia, way on the other side of France; he had made strong enemies of the Dutch in the Second Anglo-Dutch War (or the Tweede Engelse Oorlog); and lastly, he was useless at business and happy to leave the details to others. Plus he had the King's ear. Four things. So Radisson and Groseilliers wooed him, he wooed the King and in 1670 King Charles II signed into being the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson's Bay - the Hudson's Bay Company.

The newly formed HBC had exclusive (British) rights to a vast territory - all of the lands and rivers that drained into Hudson's Bay. This was essentially all of the land that would become Canada from Labrador, through northern Québec and Ontario, western Ontario, all of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, half of Alberta, and bits of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and the States. An area five times the size of France, and it was all called Rupert's Land, after the HBC's first Governor and royal patron. Of course, claiming land and actually owning it were different things, and so much of Rupert's Land was also referred to as New France, depending upon whose map you were looking at. At least until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, but I'm getting ahead of myself. In any event, in 1670 the British got into the fur business in a big way. They had a much different business model than the French - instead of travelling out into the wilderness and integrating into the local populations, the British built a few forts here and there and invited the locals to come to them. As a result, the HBC had much less effect on the exploration of Canada than the French, whose coureurs were quite busy indeed exploring ever deeper into the woods.

But they were also becoming uncontrollable. The coureurs were simply ignoring the monopoly of the Cent Associeés, who eventually went bankrupt as a result and were taken over by the crown corporation la Compagnie des Indes occidentales, the Company of the West Indies, which was in charge of the West Indies plantation trade, the African slave trade, and all beaver and moose pelts coming out of New France. They had a more lenient attitude towards independent traders, because their whole thing was supplying the plantations with slaves and goods. So it was suddenly much safer to be a coureur, and since there really weren't that many coureurs in the bush at any one time there was plenty for all. Until the population explosion that is.

Now that New France was effectively being run by those whose interests lay far to the south in the plantations, there was a huge influx of colonists, people sent to the colony on the Crown's tab to produce timber, minerals and food to send south. The new colonists included many youths from poor backgrounds, soldiers and les Engagés - indentured servants (rental slaves). And they were all men. A young man in New France had, statistically, a one in seven chance of getting a wife. And a much lower chance of securing a well paid job. As the youths matured, as the soldiers reached their discharge date, and as the indentured servants completed their contracts, there was an increasingly large number of men looking for easy money and women. Overnight, there was an explosion in the numbers of les coureurs, and subsequently, of furs. Which brought about a sharp lesson in economics.

Beaver prices tanked. There were too many furs in the market. Rather than preventing young men from becoming coureurs, however, this simply made them travel further inland into the pays d'en haut to get ever cheaper furs. So there were even more furs, and they were worth even less. An economic crisis was looming. So the French Minister of Marine (who was in charge of everything that took place on French soil that wasn't actually France), Jean-Baptiste Colbert, set about implementing a new congés system for furs which essentially meant he sold a fixed 25 licenses per year to merchants, who would then hire hardy souls to travel inland to trade for the furs. While you couldn't control the coureurs, you could control the merchants in Montréal to whom the coureurs would have to sell their wares, and this was the purvue of the Domaine de l'Occident, the Company of the West (or Farm), who had taken over from their defunct predecessor, the West Indies people, in 1674. Sadly, the economic collapse of the fur industry would continue anyway, reaching its peak in 1696 when the French fur trade was actually suspended. But then it became apparent that former French allies were simply trading with the British, with whom France was generally at war. So Québec had to restart the fur trade even though they were simply stockpiling furs in France until the prices rebounded. Fortunately for everyone involved, it turns out you cannot store furs indefinitely, and the rats and bugs of Paris fixed the oversupply problem for the French. But I digress; that was much later. Back to 1681.

The congés system was the beginning of the Voyageurs (travellers) - sort of hired coureurs de bois. And since it was being run by merchants with dozens of employees and a large bankroll, the business model inevitably changed. Instead of one or two hardy individuals trading for furs as far west as their resources allowed, and then turning around and heading back to market at Montréal, the new model had dedicated teams far into the woods who would collect furs at a series of depots, which would then be visited by other teams for transport back to market. So the voyageurs had a much greater range. And the teams were well paid. A voyageur could earn upwards of 500 livres for wintering far to the west. At the time, a day labourer in New France could make one or two livres per day, but generally only for harvest or other short periods of time. And the people paying them also owned the company store. So 500 livres paid to a voyageur at the end of the year was roughly 500 more than the day labourer had at the end of that same year. And what did the average voyageur do with all of this wealth? According to one:

"I could carry, paddle, walk and sing with any man I ever saw. I have been twenty-four years a canoe man, and forty-one years in service; no portage was ever too long for me, fifty songs could I sing. I have saved the lives of ten voyageurs, have had twelve wives and six running dogs. I spent all of my money in pleasure. Were I young again, I would spend my life the same way over. There is no life so happy as a voyageur's life!"

Those who stayed closer to home were living a slightly less glamorous lifestyle, and so were only paid 200 livres or so, still a goodly fortune paid at the end of a year with no expenses. These voyageurs would do a milk run of sorts between Montréal and the postes du nord - one on the Nipigon River by present-day North Bay, one at the mouth of the Michipicoten River by present-day Wawa, and the last at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River, which in 1681 was the jumping off point for fur traders heading west and furs heading east, and also for royal pardons being pushed out into the diaspora, into the interior wilds of the continent, as far as 120 leagues inland.

Over the years, the Kaministigouian region was literally central to ever more adventurous explorations. In 1685, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, built Fort Kaministiquia as well as forts or posts in such disparate locations as le Grand Portage, a good day's paddle south and west from Kaministiquia, another near present-day Duluth (a corruption of du Lhut) in the States, one more on Lake Nipigon and another between Lakes Erie and Huron at present-day Port Huron, Ontario. He was looking for the Vermillion Sea, likely the Great Salt Lake.

A few years later, Jacques de Noyon used Kaministiquia as a base to travel as far west as Rainy Lake. The post was abandoned with the collapse of the fur trade in 1696. But when the French rodents and bugs sorted that problem out in 1717, the fur trade was back in operation, and so was the original quest from the 16th century, to find a trade route to the Orient. So Zacharie Robutel de la Noue went off in search of the western sea, stopping off at Kaministiquia long enough to repair the Fort. Later, in 1728, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye, started using Kaministiquia for his explorations. La Vérendrye deserves a whole story of his own, which he may get another day. But in this story we'll just say that he and his sons and his engagés made it as far west as the Rockies over the course of several adventures.

And so Kaministiquia played a pivotal role in French explorations to the west. Even when it was determined that the Grand Portage route into the interior was the better route, Fort Kaministiquia was still the base of operations. Right up until the fall of New France in 1760. Which brings us to the North West Company.

In 1763, the Seven Years' War was wrapping up and France was ceding all of New France (minus Louisiana, which is a murky topic) to the British. That meant that the coureurs and voyageurs were suddenly out of a job. But there was still all of the infrastructure in place in Montréal to run a vast fur empire, complete with wilderness posts and forts in various places such as Kaministiquia. So the Pedlars, independent English fur traders, took up the slack, and by 1783-4 they were sufficiently organized to create the North West Company to directly compete with the Hudson's Bay Company. They continued the voyageur model of forts and away teams, but by this time the superior Grand Portage route into the interior had replaced any efforts out of Kaministiquia, and the Montréal teams would meet with the over wintering teams in the fort at Grand Portage, just a couple of miles the wrong side of the present day border.

Notable explorers of the North West Company include Alexander Mackenzie, who followed the Grand River (subsequently renamed the Mackenzie River) all the way to the Arctic Ocean. A few years later he travelled along the Peace River, then overland through the mountains all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Koo-koo-sint, the Star Gazer, known to some as David Thompson, travelled the equivalent of more than twice around the world, exploring the nooks and crannies of North America and making maps. Simon Fraser's interests lay in what would become British Columbia, and he built the first settlement there. All of these expeditions used the fort at le Grand Portage as a jumping off point. But then, in 1812, the Americans invaded.

After the unpleasantness of the War of 1812 was over, the North West Company was free to continue using la Grande Portage as a base of operations, even though it was now technically a part of the States and therefore across the border. They would just have to pay userious duties. So the almost forgotten Kaministiquia route, upriver through a gruelling portage around Kakabeka Falls, and thence, by a series of rivers and beaver meadows to Rainy Lake, and thence on to the Assiniboine River some 120 leagues inland, and totally within British territory, was reopened. Fort William, after William McGillivray, chief director of the company, was built on the former site of Fort Kaministiquia at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River, and using it as a base to expand inland, the North West company was able to successfully compete with the Hudson's Bay Company. They eventually merged with the HBC after some violent confrontations, but this story is not really about the fur trade. It is about Fort William. Which brings us to Port Arthur.

A few miles north of Fort William, and a few years after Confederation, the Department of Public Works built a depot to facilitate the building of its road all the way to the Red River Colony, which you might call Manitoba. The Lake Superior terminus of this road was called Prince Arthur's Landing, after Queen Victoria's son, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn. With the completion of the road, and subsequently, the railroad, Port Arthur (the original name was dumb, so they changed it) became the vitally important trans-shipment center that Fort William had been, this time for grain rather than furs. By 1884, between the road, railroad, grain elevators, Great Lakes shipping and even a silver mine on the Sibley Peninsula, the town of Port Arthur was booming. And then it wasn't.

In 1889 there was a bit of a skirmish between the town of Port Arthur and the Canadian Pacific Railway. The town thought the CPR owed a bunch of back taxes; the railway's position was nuh-uh. When the town seized a locomotive, the railway responded by moving all of its operations, including rail yards, coal facilities, grain facilities, the machine shops necessary to the running of a railway and hundreds and hundreds of employees to the nearby village of Fort William, which was delighted. Between the loss of the CPR and the collapse of the silver market a year later, Port Arthur was in dire straits. Then the Canadian Northern Railway chose the town as its base for the movement and trans-shipment of their grain from Winnipeg, and the town was suddenly back in business.

The duality of the two towns continued for many years. When the Port Arthur Pulp and Paper Company started operations, within 3 years there was a Kaministiquia Pulp and Paper Company. The Canadian Northern Railway was absorbed into the Canadian National Railway, and the route through Port Arthur was downgraded in favour of Fort William. But the western grain companies preferred the somewhat sheltered bay to the north, closer to Port Arthur, as the location for their new larger grain elevators. And so things were sort of back and forth, and meanwhile, the two towns were expanding and a merger was inevitable.

On January 1st, 1970, the two towns became the new city of Thunder Bay. There was basically no issue to the merger, just the name. In the referendum held to determine the name, the Thunder Bay crowd voted 15,870 in favour of that name. The Lakehead crowd numbered 23,679. So Lakehead was the winner. Except whoever ran the ballot also put The Lakehead on the ballot, which siphoned off 8,377 of the purely Lakehead votes. So Lakehead lost to Thunder Bay by 568 votes. And Thunder Bay is what we call the city to this day.

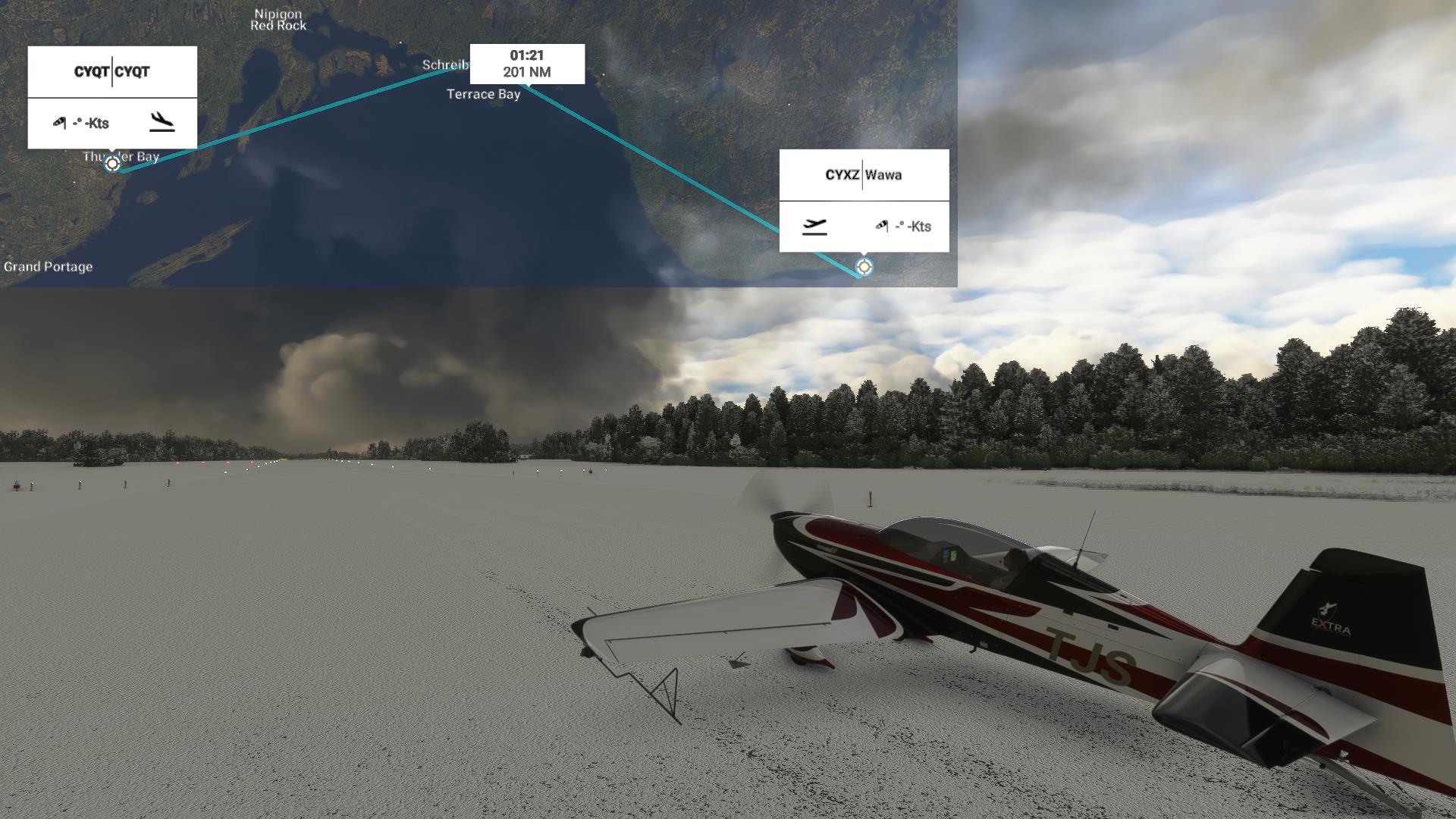

The weather's a little sketchy to the east. Luckily we're going west.

The weather's a little sketchy to the east. Luckily we're going west.

|

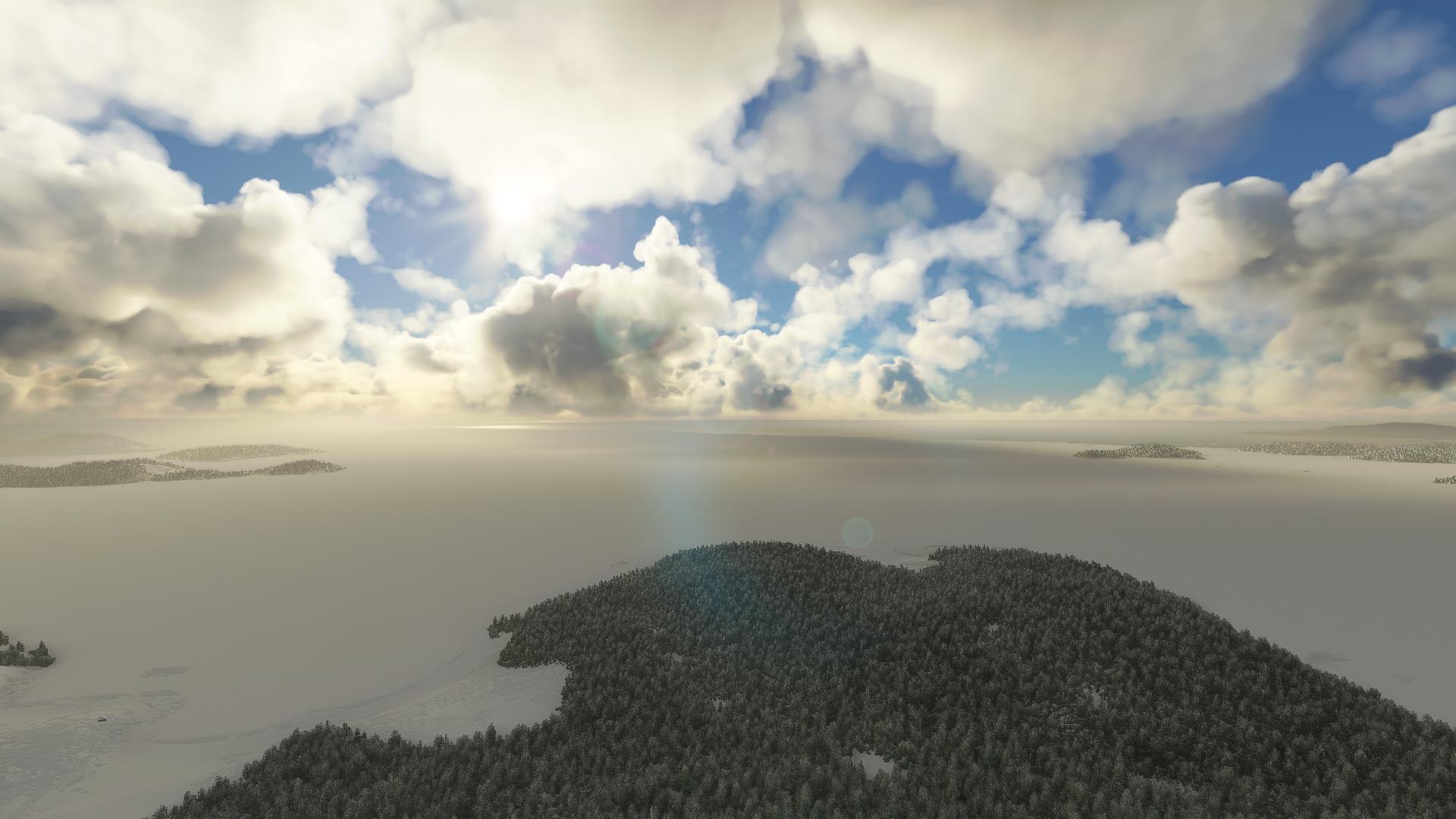

The ice is firming up. Lake Superior hasn't frozen completely over since 1996 though it comes close from time to time.

The ice is firming up. Lake Superior hasn't frozen completely over since 1996 though it comes close from time to time.

|

Red Sucker Point, approaching Neys Provincial Park. This area is actually a one billion year old volcano.

Red Sucker Point, approaching Neys Provincial Park. This area is actually a one billion year old volcano.

|

Terrace Bay, so called because of the many shorelines, or terraces, created as the water level dropped after the last glaciation. Like so many northern towns there is only one main employer, a pulp and paper mill in this case, and the town's fortunes ebb and flow in sync with those of the mill.

Terrace Bay, so called because of the many shorelines, or terraces, created as the water level dropped after the last glaciation. Like so many northern towns there is only one main employer, a pulp and paper mill in this case, and the town's fortunes ebb and flow in sync with those of the mill.

|

Sibley point up ahead. The town and old silver mine of Silver Islet to the left and the Sleeping Giant in the far background.

Sibley point up ahead. The town and old silver mine of Silver Islet to the left and the Sleeping Giant in the far background.

|

Just passed over Sibley Point. If you look back and squint a bit you can make out the form of Nanabijou, Spirit of the Deep Water. He rewarded his Ojibwe people with the gift of a fabulous silver mine but told them to never divulge the secret location. Of course word got out, and Nanabijou turned to stone, dooming his Ojibwe people to living outside the spirit's favour. The Silver Islet Silver Mine has a story of its own that we might get into if we're ever back this way.

Just passed over Sibley Point. If you look back and squint a bit you can make out the form of Nanabijou, Spirit of the Deep Water. He rewarded his Ojibwe people with the gift of a fabulous silver mine but told them to never divulge the secret location. Of course word got out, and Nanabijou turned to stone, dooming his Ojibwe people to living outside the spirit's favour. The Silver Islet Silver Mine has a story of its own that we might get into if we're ever back this way.

|

Kamanistiquia river, with its islands to the right. The actual location of the fort is buried under town now, but would have been here somewhere.

Kamanistiquia river, with its islands to the right. The actual location of the fort is buried under town now, but would have been here somewhere.

|

And that's a wrap for Thunder Bay, the gateway to the interior. So let's travel into the interior and see what's there.

And that's a wrap for Thunder Bay, the gateway to the interior. So let's travel into the interior and see what's there.

|